Soz for the delay, life happened. Even my boss reprimanded me for failing to deliver yesterday.

I’m still waiting for him to deliver on a 2x raise. So.

Today’s post is based on a request from a welcome email survey response to talk about rosé. So as it’s still the season, I’m bumping the topic I had planned for today to give the people what they want 😘

BTW, the survey is truly anonymous (#GDPR), so if your suggestions lack context, I can’t act on them AND I can’t reply with follow-up questions 😢

Instead of bringing you a top-ten list of rosé styles, where to buy them or what they go with (here are some links though if you are interested: ten styles, how it’s made, 4 most popular rosé varieties, best rosé brands), I thought it’d be more interesting to do a little story time on a less-appreciated rosé: White Zinfandel (“Zin”). If there is any wine that is truly Californian, it is this.

Unless you’re American, chances are you probably haven’t come across White Zin, which might not be the worst thing ever since it’s more like fruit juice than anything. However, it redeems itself in a story that includes happy accidents, fraud, and saving precious old vines.

This post is dedicated to my Great Aunt Glessa (RIP), who aside from being the family’s sneakiest May I? player, famous lemon meringue pie maker, and gift wrap bow collector, was rarely seen without a manicured hand wrapped around a glass of White Zin—or, "blush”—typically from a growler of Carlo Rossi or a bottle of Sutter Home or… “any brand”, really. No ice.

If you’re new here, welcome! Join the fam:

Don’t forget you can check out my other posts and follow me on Instagram @thirdplacewine, and LinkedIn, too.

Today’s post is brought to you by… ViaTravelers

One of the great things about wine is that it goes well with travel.

If you’re like me, planning a trip involves a Google spreadsheet and a lot of browser tabs. If you’re not like me… I don’t know how you do it.

ViaTravelers is a resource for both planners and non-planners. Their travel guides are resources for planning inspiration, or for checking in situ if you’re more inclined to go with the flow.

To subscribe, click here. If you’ve received this post in your email, you can join in one click using the button below:

Photo by Mathilde Langevin on Unsplash

Zinfandel in California

You can’t talk about White Zin without first talking about the history of Zinfandel in California.

Zinfandel is a black grape with origins in Croatia where is it known as “Crljenak Kastelanski” or “Tribidrag”. However, Zinfandel is grown primarily now in only two places: Italy (in Puglia) where it is called “Primitivo”, and California, where it is called “Zinfandel”.

Zinfandel first came to the US in the 1820s, through a Long Island, New York nursery owned by George Gibbs, who brought cuttings from the Imperial Collection of Plant Species in Vienna, Austria.

By 1845, it had become popular and Massachusetts nursery owner, Frederick Macondray, decided to bring vines to California ahead of the Gold Rush (1848-1855).

Zinfandel did well in California not only because it took well to the environment, but also because in post-Gold Rush California, the traditionally head-trained vines didn’t require any special equipment or precious resources, such as timber or wire.

It also was among the first vines replanted on rootstock in the 1880s after many vineyards were decimated by phylloxera, so that by 1888 over one-third of vines were Zinfandel. During this time, a number of Italian immigrant families took the lead in growing and making Zinfandel, among which is the Martinelli family (no, not the sparkling apple cider family) which still operates today.

In the 20th century, Zinfandel managed to survive the Great Depression (1929 - 1939) and Prohibition (1920 - 1933) by supplying grapes to local home winemakers. However, a number of vineyards were still ripped up and recovery for Zinfandel following this period was slow going as most surviving vineyards were not high quality and their grapes were blended into obscurity.

It wasn’t until the 1970s, when White Zinfandel was “invented” by accident, that things started to look up.

How White Zin became a thing

White Zinfandel as we know it today is off-dry to sweet, but originally it was a dry rosé. To understand the evolution from dry to off-dry/sweet, a little background on the main styles of California red Zinfandel is necessary.

In California, red Zinfandel is usually made in one of two styles: a lighter, “Claret” style (think Ridge winery), or a richer, “Port” style. It’s the “Port” style that is the most popular and widely available, which I find unfortunate—it’s generally big, flabby, and hot (14-17% ABV)—like drinking a jar of blackberry jam. (Primitivo doesn’t do much better, IMHO… it’s a pepperier blackberry jam.)

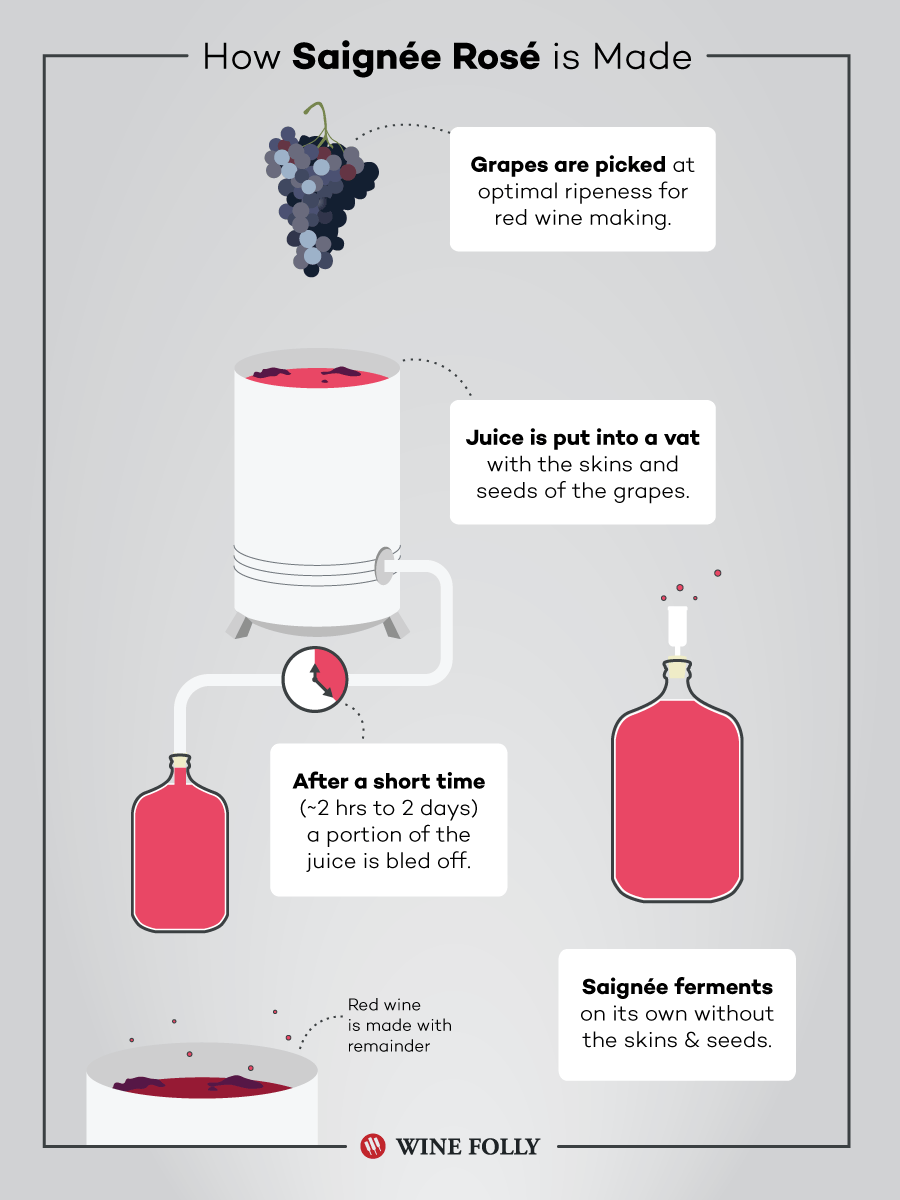

Why does this matter? Because to make the “Port” style, winemakers often use a method called “saignée” (“bleeding”) to concentrate the wine. They do this by “bleeding” off some of the free-run juice from the skins, leaving behind a more concentrated juice to ferment into red wine (higher proportion of skins to juice = more flavors and tannins in the resulting wine). The bled-off juice, slightly pink from skin contact, is separately fermented like a white wine to dryness, creating rosé.

So, White Zinfandel started as a dry rosé. The first documented was made in 1869 by George West of El Pinal Winery in Lodi, California, although it is Bob Trinchero of Sutter Home who is credited with creating it in 1975.

Bob’s success a over century later (which I’ll get to below) can perhaps be attributed to a few additional advantages that George West didn’t have. The first is Mateus (yes, the sweet Portuguese rosé) and the second is an influential grocer from Sacramento, Darrell Corti.

From the 6th century BC until the 19th century AD, rosé, predominantly dry and French, enjoyed a rather good reputation. In 1943, two sweet Portuguese rosé wines, Mateus and Lancers, came on the market. Their success accomplished two opposing feats concurrently: they destroyed rosé’s reputation and primed the market for Bob Trinchero’s White Zin.

When these sweet Portuguese rosés hit the market, they were a novelty. Sales boomed. Eventually, people came to believe that all rosé was sweet and inexpensive, no serious wine drinkers drank rosé as a result. The reputation of pink wines suffered, and so did sales.

Following an attempt to revive the brand with a big advertising campaign featuring people like Jimi Hendrix and the Queen of England, Mateus came back into fashion. After democracy was restored to Portugal following the 1974 revolution, the US imported 20 million cases of Mateus for its American fans.

It was during this period that Bob Trinchero was making red Zinfandel, concentrating it via saignée method and fermenting the free-run juice into a dry rosé wine. This was 1972.

The rosé he made was called “Oeil de Perdrix” (“partridge eye”) which is a French term for white wines made from red grapes. US law required an English description though, so “a white zinfandel wine” was included on the label. “White Zinfandel” was born, but it was still dry!

(Fun fact: “Oeil de Perdrix” comes from Champagne during the middle ages, where the pink color refers to the color of a partridge’s eyes in death throes…French!)

Bob kept some of this rosé for his tasting room and sold half to Darrel Corti, who aside from being “just” a grocer, was also something of a connector in the wine and gourmet world.

Bob kept making his dry White Zinfandel until a fateful day in 1975, when the fermentation of his White Zin stuck. Stuck fermentation is when fermentation doesn’t complete so not all the sugar is converted into alcohol. The resulting wine had 2% residual sugar—it was sweet. Bob decided not to fix it and bottle it instead. Darrel Corti also decided to roll with it and carried some in his store, Corti Brothers.

The White Zin flew off the shelves. By 1985 Sutter Home had sold 1.5 million cases. By 1987, they sold 2 million cases and it became the best-selling premium wine in the US. As a sweet, low alcohol, approachable wine, White Zin was responsible for bringing a lot of people to wine—a “gateway wine” so to speak.

The demand was so high that it outstripped the supply of Zinfandel grapes, including old vines (imagine old vine Zinfandel being used to make White Zin!). It outsold red Zinfandel 6:1 and at a point it was the third most-popular wine in the country by volume.

To get in on the action, some winemakers started making fake White Zin, passing off other, cheaper grapes as Zinfandel. The most famous case involved Fred Franzia, the nephew of Ernest Gallo and founder of Bronco Wines.

In 1994, Fred Franzia pled guilty to federal charges of conspiracy to defraud, labeling Carignan and Grenache grapes as Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel, misrepresenting 5,000 tons of grapes and millions of gallons of wine.

(NB: Fred Franzia does not control the famous Franzia boxed wine brand, although it was his family’s. They lost control of their name when they sold their business, Franzia Brothers Winery, to The Wine Group in 1973.)

Saving old vines

White Zin’s wild commercial success can be credited for saving old Zinfandel vines in premium areas such as Dry Creek Valley (Sonoma) and Russian River Valley (Sonoma). A lot of those vineyards exist today because they were able to sell to White Zin makers in the 1980s and 90s during a time when growers were also privileging fashionable Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay following California’s triumph over the French in the 1976 Judgement of Paris.

Ironically, thanks to the success of a rather modest wine, some great Zinfandel producers working with old vines can operate today, among whom are:

Zinfandel rosé, the new White Zin

Despite a dip in popularity in the 2000s over White Zin and its cheap bulk wine image, it still occupies an important position in Californian wine. In 2006, White Zin counted for almost 10% of US wine sales by volume (6.3% by value), and today Zinfandel represents California’s third-leading variety in acreage.

Interestingly enough, some winemakers are now reviving dry White Zins—“Zinfandel rosé”—that are picked early, with high acid and a lighter body. Two that I’m looking forward to trying during my next trip to California are:

Perhaps Aunt Glessa would approve.

If you enjoyed this deep dive, consider subscribing and sharing with a wine nerd in your life. Your feedback is also welcome [email protected].

Join the nerdery.