As they say, another day, another dollhair.

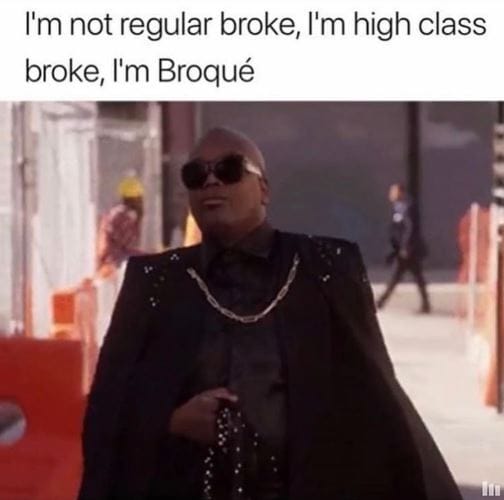

As they also say, money can’t buy class—but it can buy better taste, as we’ll see below. That’s good news for people who are broqué like me.

Today, I am going to talk about what it takes to develop good taste, or at least a good palate: nature v. nurture, vocabulary, and yes, money.

If you’re new here, welcome! If you like wine, join us:

Don’t forget you can check out my other posts and follow me on Instagram @thirdplacewine, and LinkedIn, too.

Today’s post is brought to you by… Beehiiv…

I write on Beehiiv, and you can too. Think of it as a better Substack. Lots of good stuff packed into one platform, and the team is constantly shipping.

…and Flight Club

The next Flight Club will take place on 9 December and it will be based on Israeli wine. Food will be served. Minimum donation is €100 and 100% of proceeds will be donated to support non-profit efforts in Israel. For more info, see the events page.

Blind tasting is fun. It’s when you taste a wine and guess where it comes from, the grape(s) used, its age and quality. Even watching people blind taste and trying to guess what they’re drinking from their notes before they make their final calls is super fun. Some people can even name the producer, parcel and exact vintage! I know, nerds.

If you’ve ever seen videos on the interwebs of people blind tasting, or even watched the documentary SOMM (which is how I was first introduced) and wondered “what is this wizardry?”, wonder no more.

Nature v. Nurture

Blind tasting seems magical but it comes down to training and theory, both which you practice and learn when you study wine. In WSET, one of the first things covered is a structured approach on how to taste and evaluate wine. As you move through the levels, you taste wines of increasing complexity and quality and learn to draw conclusions about them. Starting at level 3, this skill is tested by blind tasting.

You don’t have to have a good nose or palate in order to start—I don’t (nobody’s perfect)—although it makes life a lot easier. In fact, one of my most amusing memories from WSET is when my French instructor, who teaches socratically, lost his patience as I took too long to pinpoint different aromas.

Déborah.

Déboha.

DÉBOHHHAAAA!!! …will you tell us what you smell?!

The thing is, your palate is like a muscle you have to work out. Some people are naturally fit, others not so much. For the others, you simply have to go to the gym more.

In my case, I learned I am naturally stronger at evaluating structure, balance and aging potential than articulating aromas and flavors, so I have to work on the latter. With training in class, my palate vastly improved in accuracy and speed to the extent that I even surpassed my classmates who were more advanced in the beginning—I was among the few that passed the blind tasting portion of the exam.

(Unfortunately, your palate does decondition just like muscles atrophy if you don’t use them regularly.)

The important thing to know is that everything about wine leaves clues, you have to learn how to read them. When you watch someone blind taste, unless they know exactly what they’re drinking from the jump, they’re likely following a process of elimination that looks more or less like this:

Is it old world or new world?

Is it from a warm climate or cool climate?

What do I see/smell/taste that can narrow down the likely grape and age?

What do I know about various wine regions, their climates and laws to eliminate options about place?

What do the complexity, intensity, structure and balance lead me to conclude about quality and aging potential?

The takeaway: If you’re not naturally fit, go to the gym. Wine Folly’s Wine Tasting Method video is a good place to start.

Vocabulary

Cat’s pee on a gooseberry bush

Geraniol

Petrichor

Having a wide, creative vocabulary is useful not only for general intelligence and classiness, but especially for communicating about wine. It is therefore important as part of your wine tasting training to not only expand your palate but also your vocabulary. The descriptors above won’t mean anything to you unless you’ve actually smelled or tasted them. They certainly won’t mean anything if you don’t even know what those things are. Language matters.

BTW, here’s what those notes mean:

“Cat’s pee on a gooseberry bush” is a note about New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc attributed to two wine critics, Jancis Robinson and Oz Clarke.

“Geraniol” is a terpenoid that smells herbacious and vegetal …like a geranium. It’s a fault in high quantities.

“Petrichor” is the smell after it rains.

To develop your nose and palate, smell and taste everything, and I mean everything (OK, don’t go tasting cat’s pee, but if you smell it it is unmistakable!). For example, when you go to the market, smell and taste the produce as well as their leaves and flowers, and also smell and taste flowers and spices. Their flavors and aromas can exist in wine, too, and often point to important clues.

For example, “green bell pepper” commonly crops up in descriptions about Cabernet Sauvignon, specifically old world, and more specifically left bank Bordeaux. This note comes from a pyrazine in Cabernet Sauvignon, so if you were to get this note in a blind tasting and went on to conclude that it is a Tempranillo from Spain, you would be definitively wrong.

To expand your vocabulary, read. There are many commonly agreed-upon terms in the wine world, but descriptors can also be highly personal. Certain aromas and flavors may hold a stronger memory for you, so you can also come up with your own that help you identify things—be creative. Some of mine are:

Bricky: referring to how green tannins are—imagine how your tongue would feel if you licked a brick. The range is “bricky” to “quite bricky”.

Narnia wardrobe: refers to a musty, dusty type smell or flavor. I usually experience it in old world reds (usually Bordeaux or Burgundy with some age) but also in less-fruity versions of whites like Malvasia and Sercial. I may also use this interchangeably with, “Grandma’s closet”, which is less magical and more… dusty.

Jura: refers to my ex-boyfriend’s dog, Jura, when she needs a bath and is smelling just a little piquant and tangy. It comes up for me in some reductive wines.

These terms are a useful shorthand for myself, and you will likely come up with your own, too. You just might have to explain them to other people in commonly agreed-upon terms for them to understand.

The takeaway: To sharpen your palate, sharpen your words.

Money, money, money

@Cédric, I am waiting for my 2x raise.

At the end of the day, you need to taste. A lot.

At a certain stage, even if you’ve autodidacted your way to a decent palate, you will need money. That’s because it takes money to buy the things and experiences to develop it. Access is a harsh reality.

You can begin though in a cost-effective way by going to as many different tastings as possible. These are often organized around a theme (types of wines, regions, vintages, etc) at expos or by various wine bars and merchants.

You can also organize tastings yourself among friends and split the bottles. However, if you’re still learning and calibrating your palate to commonly agreed-upon wine terms, it’s better to attend events where you can have some guidance. Some wine bars even offer flights where a sommelier will go over your notes and give feedback.

However, once you get to a decent stage in your tasting abilities, it makes sense to spend the money to travel to wine regions to better understand the place, to see how things are made by the very people who make them, to taste with them and to eat the local food that goes with it.

It’s also worth seeking out benchmark wines which provide useful signposts for comparing styles of wine and quality. If you can manage, there really is no better way to learn than to taste benchmark wines with their producers or a true expert.

The takeaway: To learn how the sausage is made, go to the factory. (Corollary: Money helps. A lot.)

We like to think that we are above the influence of marketing or branding, but we absolutely are not. Being able to taste blind is not just fun party skill, it also helps you to objectively determine if a wine is actually good or just hype. It requires you to go to the gym, to sharpen your vocab, and to learn how the sausage is made.

Money might not be able to buy class, but it can help buy a better palate. And hey, maybe it can help you be classier? After all, getting good at wine can help you roll with some classy peeps. Just be forewarned: working out your palate is a never-ending exercise, and that’s probably the best part about it all. The only risk is that your taste may eventually exceed your budget!

If you enjoyed this, consider subscribing and sharing with a friend!

Join us - the more the merrier!